Early this year, Jesse James Garrett tweeted about process:

Always disappointed when I hear that people think @AdaptivePath is militant about process. You won’t find a more anti-process design firm.

— Jesse James Garrett (@jjg) January 29, 2014

This appears to contradict the title of this post, so to give you some more context, I should explain that Adaptive Path is a user experience design and consultancy firm, and show you followups and replies in the twitter conversation that followed:

In fact, I’d argue that nobody can develop new methods if they’re in the habit of strictly adhering to them.

— Jesse James Garrett (@jjg) January 29, 2014

.@chsweb A solution only works every time if the problem is the same every time.

— Jesse James Garrett (@jjg) January 29, 2014

From a user experience consulting and design perspective, this makes perfect sense – analysing what each particular customer and their users need, and how they interact, will by necessity be different every time. However, it also hints at the inherent complexity that you will sometimes find in web application development. Because from a software development perspective, you need to be Schrödinger about process.

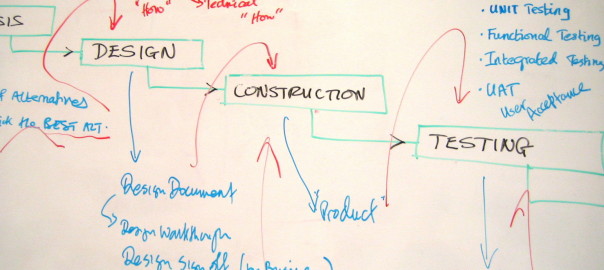

To clarify: at a high level, you need to ruthlessly follow the software development process – gather requirements, design, implement, test, release, repeat. Sometimes, there will be pressure to skip one of the steps. For example, starting implementation without designing first. As I wrote last week, this will cost you. Similarly, in Agile environments, and at a lower level, there is sometimes pressure to change the definition of a Sprint once started. This misses the point of an Agile approach – it is between Sprints that priorities should be changed, and the incremental iterations will produce the desired result. Changing priorities within a Sprint will confuse the team or corrupt work allocation, potentially elongate the Sprint delaying the release, or even produce unreleasable code – it moves you away from “Release Early, Release Often”.

At the same time, you must constantly refine, or change, your process. In Scrum, this is done at the Scrum retrospective, by asking what went well and what could be improved. The theory is to continue doing what went well, and to change or avoid what didn’t. The complexity I mentioned comes into play here. There needs to be context to what you continue to do, and what you stop doing. If implementing a design from a third party didn’t go well, the answer is not necessarily to avoid third party designs altogether – it may be that you need to avoid that particular third party, or that you need to discuss the design requirements with third parties, or any number of possibilities particular to the situation.

Different aspects of product development will necessarily have different processes for achieving their goals. In web application development, requirements gathering of the design, functionality, architecture, and user experience/acessibility/usability of the product could all have different processes. Coordinating the implementation aspects and processes is logistically complex. If the processes which are in place are not followed, it is entirely possible that that coordination will be lost, and your team will end up at a standstill.

Photo by Matthew Burpee via flickr.